Winold Reiss will not be classified.

April 12 – May 25, 2018

Even during his lifetime, and at the height of his career, the extraordinarily successful German-American artist Winold Reiss (1886–1953) defied categorization. Was he a fine artist or a designer, illustrator or architect, printmaker or muralist? Steeped in the German arts-and-crafts tradition with its permeable boundaries between fine and applied arts, Reiss bucked the hierarchical world of American art by practicing a broad array of artistic disciplines with an excellence and panache that few could rival. Upon visiting the artist’s bustling art school and studio abounding with Reiss’s own portraiture, landscapes, abstractions, graphic work, illustrations, interior and exterior studies, mural projects, furniture and fabric designs, the writer P. W. Sampson began his 1931 feature on the artist with a simple conclusion: "Winold Reiss will not be classified.”[1]

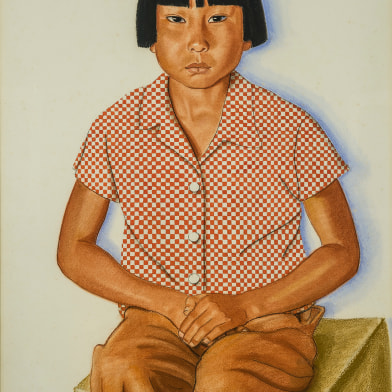

Hirschl & Adler is pleased to present the first comprehensive gallery exhibition on Winold Reiss in more than 30 years. Featuring 40 works from across the artist’s four-decade career in the United States, the exhibition seeks to capture the full range of Reiss’s celebrated versatility through his oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, prints and drawings. Today the artist is perhaps best known for his dazzling and innovative portraits of the Blackfeet Indians in Montana and of other figures from the American Wild West that had so captivated him in his youth. Separated Spear Woman with Headress, of 1936, commissioned—like many of his Native American subjects from this period—by the Great Northern Railroad, typifies the virtuoso rendering and dignified portrayals that make Reiss among the greatest chroniclers of 20th-century Native Americans.

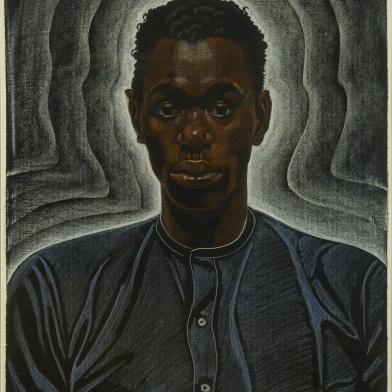

But Reiss’s accomplishments back in New York are being rediscovered as equal in importance to his Western work. Scholarship is increasingly focused on Reiss’s seminal role developing the fine arts component of the Harlem Renaissance. More than ever he is appreciated as the teacher of artist Aaron Douglas as well as an influential interpreter of America’s jazz aesthetic. Starting in 1925, Reiss painted memorable, and in some instances, iconic, portraits of such stalwarts of the Harlem Renaissance as Langston Hughes, W. E. B. DuBois, and Zora Neale Hurston among a host of others. But not all of Reiss’s portrait subjects were prominent figures. As he had always done, in all the places he traveled and worked, Reiss painted portraits of people whose faces “spoke” to him. Portrait of Sari Price Patton, 1925, reveals a young woman who is the epitome of chic—strikingly attractive, tastefully coiffed and elegantly dressed in keeping with the latest standards in refined jazz-age beauty. Serious and self-possessed in mien, Patton is very much a representative of the elite strata of Harlem society, a group that was widely expected to generate the leadership that would lead the American Negro to an approaching future of legal equality and equal economic opportunity.

While Reiss’s portraiture was important to the Harlem Renaissance, it was by no means his sole contribution to this seismic cultural upheaval. He was also the teacher of Aaron Douglas (1899–1979). The style that Douglas devised under Reiss blended influences from African sculpture and masks along with contemporary European currents like cubism. Douglas went on to become the iconic artist of the Harlem Renaissance. Reiss’s modernist incorporation of African art forms into his contemporary designs permeated the entirety of the Harlem Renaissance’s visual aesthetic. Interpretation of Harlem Jazz I (private collection) along with Untitled are among a group of his so called “imaginatives,” ink drawings that convey the brio, the exhilaration, and the urbanity of jazz in graphic form. The inclusion of African masks and other forms signal Reiss’s ethnographic interest in non-Western arts and cultures, and his belief that a new American art could be formed out of their artistic traditions.

Reiss’s murals in New York for the stylish restaurants Crillon and Longchamps, among others, and especially the monumental mosaics and panels executed for Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, are now celebrated as among the most accomplished and dynamic American public artworks of the 20th century. The spectacular Cincinnati murals, translated into mosaic at his insistence, explicate the history of that city within the greater panorama of America’s story. Installed in 1933 in the midst of desperate economic depression, these mosaics lit up the concourse of the Cincinnati Union Terminal, their brilliant colors and shapes punctuating the walls between windows and doorways that led to the railroad platforms. Original Painting for Cincinnati Union Terminal Murals: Inks, Printing and Writing Ault & Wiborg Company is the cartoon for one of fourteen grand industrial-worker mosaics that celebrate the glory of Cincinnati financial enterprise and mechanical ingenuity. Over the years, Reiss’s beloved murals have become a focal point of Cincinnati pride.

[1] P.W. Sampson, “A Modern Cellini—Winold Reiss,” The Du Pont Magazine XXV (March 1931), p. 5.