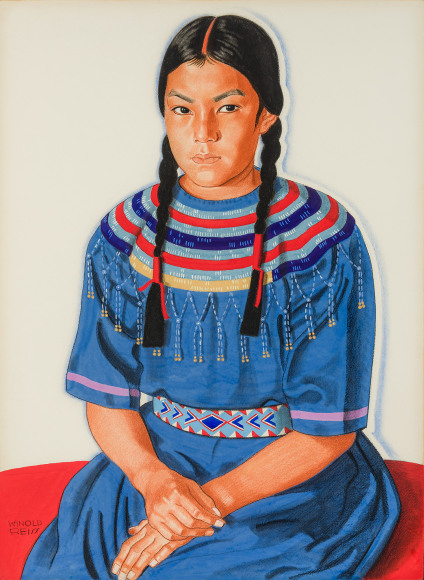

WINOLD REISS (1886–1953)

Long Time River Woman (Blackfoot Maiden), 1943

Mixed media on paper, 29 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.

Signed (at lower left): WINOLD / REISS

RECORDED: Jeffrey C. Stewart, Winold Reiss: An Illustrated Checklist of His Portraits (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, 1990), p. 76 illus.

EX COLL.: the artist; private collection, New York around 1980; [Midwestern Gallery, Cincinnati, Ohio]; to Mr. and Mrs. Michael Frost, New York, until 2024

Reiss’s portrait of Longtime River Woman is a work of 1943, an important summer for the artist. World War II seriously disrupted Reiss’s sources of income. Interior decoration commissions fell off; art school enrollments plummeted, and once again Reiss found himself identified as a German in a profoundly anti-German environment. Art materials were in short supply and travel restrictions prevailed. In 1942, Charles W. Moore took over as the advertising manager of the Great Northern Railroad, and though railroad travel and hotel business were at a standstill, Moore felt the need for a cache of portraits to use in the Railroad’s annual calendars, a way of keeping the railroad a visible presence in American life in anticipation of a return to normalcy at the end of the War. Moore was concerned that “the real Blackfeet types are vanishing,” and he was eager for Reiss to paint these native Americans. The pressure for assimilation was also making inroads into the wearing of traditional Blackfeet dress and, hairstyles, braided hair for both men and women. The railroad wanted Reiss to document “genuine” Indians for its promotional materials. Reiss’s return to Glacier National Park in 1943 was a happy reunion of old friends, both for the painter and his subjects. He produced sixty-six portraits that summer, one of which is the present Longtime River Woman.